Every so often, there’s a buzzword that grabs the imagination of the startup ecosystem. Circa 2018, it was neobanking. Suddenly dozens of fintech startups — large and small — were building a neobank.

Some raised huge seed rounds — see the case of Jupiter or Epifi. But the post-demonetisation bullishness on neobanking has crumbled. India’s neobank dream looks to be over.

Due to RBI rules, neobanks could not replace licensed banks in India, but they expanded the reach of smaller banks by acting as the digital interface and acquisition channel for the banks. Neobanking startups were like co-branded mobile banking apps for actual banks, but the degree of branding depended from startup to startup.

What these startups promised banks is that they could provide the best user experience thanks to their tech-first mindset and approach. This included automating processes and providing add-ons to enable instant account opening, low fees, customisation and niche targeting.

The latter was the way for startups to find their competitive edge by targeting freelancers, teenagers, young professionals, MSMEs, early stage startups and some international companies.

In short, they sought to make banking feel as effortless as using a UPI app. And it reduced much of the bank’s customer acquisition costs and people costs.

Then came the pandemic. As branches shuttered and people avoided physical paperwork, the shift to digital banking accelerated dramatically. Neobanking became more than just fashionable.

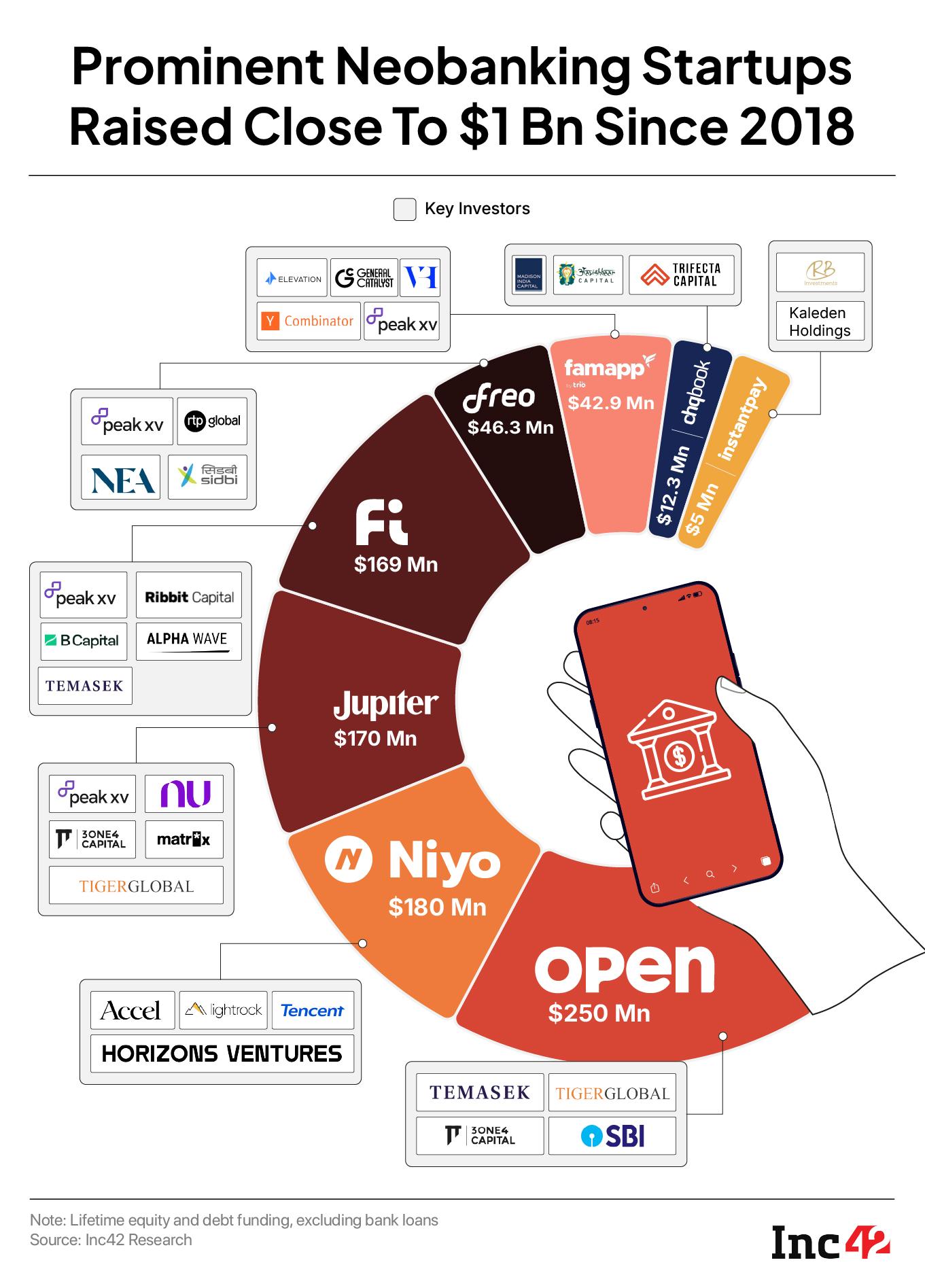

From Funding Boom To BustAs per Inc42 data, neobanking startups in India raised about billion dollars over the course of 2018 to 2023. Open famously became the 100th unicorn in India in 2023 and has raised over $250 Mn, while Jupiter has raised over $170 Mn. That’s not too far from Fi’s lifetime funding of $137 Mn. Meanwhile, the likes of Niyo raised $180 Mn, whereas ChqBook, FamPay and Freo raised $12.3 Mn, $42.9 Mn, $46.3 Mn respectively.

But it’s been a quiet few years in this space since this boom. Most of these apps today offer standalone payments experiences without a bank account. They are distributors of loans and insurance and discount broking, and neobanking has taken a backseat.

In July this year, Inc42 reported that Fi Money laid off more than 50 employees in the past three months alone. Jupiter Money meanwhile, has potentially laid off more than 70 people in the past seven months, as the EPFO data suggests. However, Inc42 couldn’t verify this at the time of publishing the story.

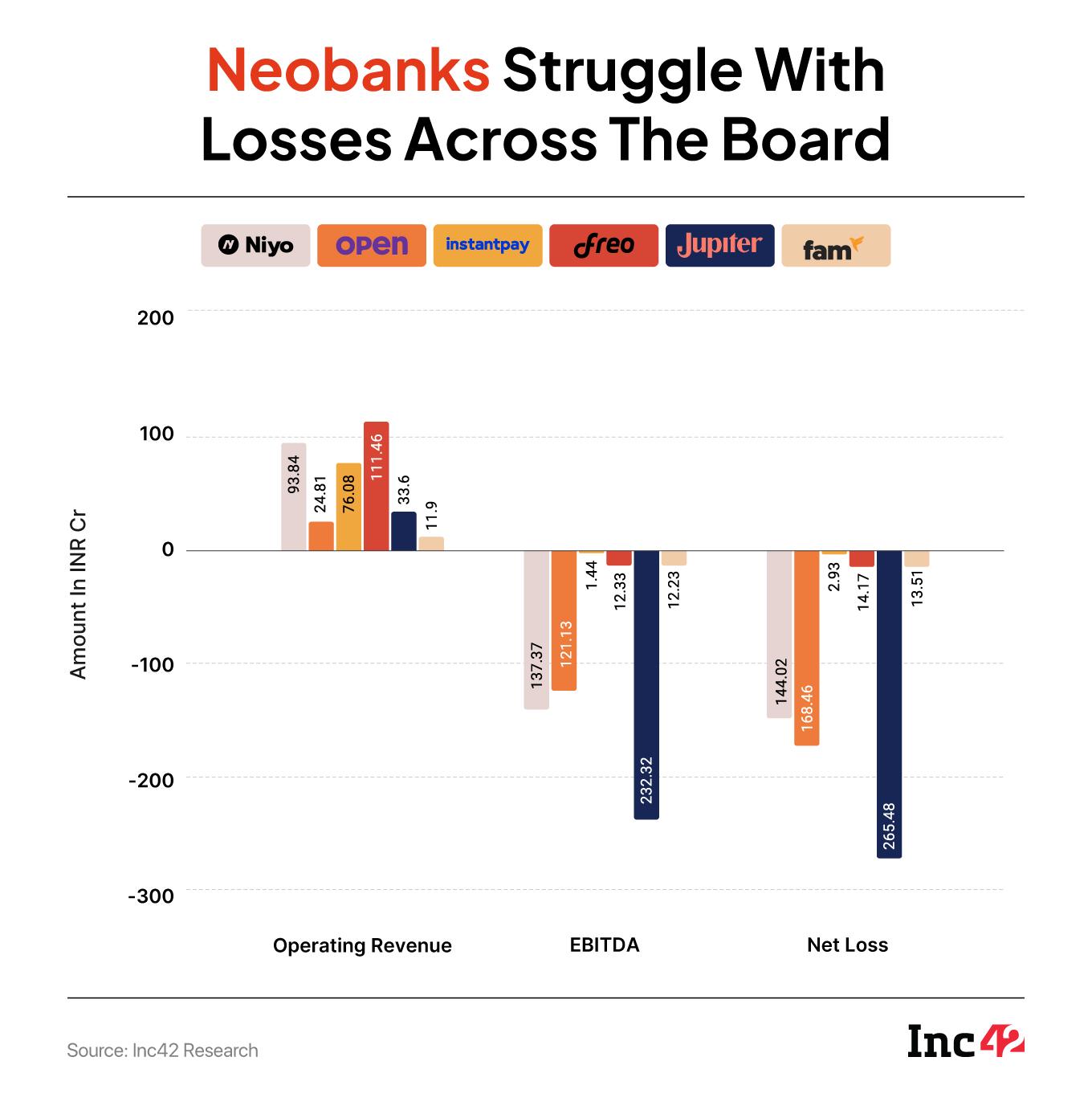

None of the startups working in the space has been able to show any meaningful revenue while the losses have gone up astronomically.

Jupiter, for example, reported a net loss of INR 276 Cr against revenue of INR 35.8 Cr in FY24. Similarly, Open earned a mere INR 24.8 Cr, on the net loss of INR 169.6 Cr.

Other neobank players have also been burning cash and carrying losses. Freo earned INR 111.4 Cr in FY24, yet ended with a net loss of INR 14.1 Cr. Niyo, a neobank which has raised over $179 Mn in funding in its lifetime, clocked revenue of INR 93.8 Cr and a steep loss of INR 144 Cr in FY24.

These numbers show that startups have not been able to unlock the revenue streams that were promised as a result of the technology, automation and product-first mindset of this category. While a lot of emphasis was placed on developing apps that had the superior user experience, neobanks struggled with lack of autonomy in operations and being forced to move in accordance with larger banks.

Incidentally, in geographies such as the Philippines, Brazil, and even the UK, neobanks are more relevant. Indonesia boasts the likes of OFBank, UNOBank, GoTyme Bank, Maya Bank and Tonik, while Brazil-based Nubank has over 100 Mn customers in Latin America and is the largest fintech bank in the region.

UK’s Revolut recently entered the Indian market in the payments space, but made a name for itself in its home turf as digital-only neobank.

A key difference in these markets is that regulators have created digital-only banking licences, while India still requires banks to maintain a physical presence. This meant neobanks in India could never truly stand alone; they had to rely on partnerships with established banks for everything from accounts to cards to compliance.

“In markets like the Philippines, regulators have issued digital bank licences. When Indian neobanks launched, many expected a similar licence would eventually come here. But it never happened,” Aishwarya Jaishankar, cofounder and COO of Hyperface, told Inc42.

Jaishankar, who led HSBC’s digital products and the launch of Kotak Mahindra bank’s ‘811’ neobanking app before launching Hyperface, said neobanks have to choose to either remain a partner-led neobank or try to get a small finance bank licence, which is extremely difficult, because the balance sheet requirements are steep.

It’s easier for a microfinance player to become a small finance bank than for a digital-first neobank, she claimed.

As per Rajjat Gulati, cofounder of plutos ONE, given the absence of a digital bank or neobanking licence in India, these startups are effectively distribution partners for all kinds of authorised banks. “This means that they have a high bar for compliance but limited visibility on revenue,” said Gulati.

Jaishankar added that this is why neobanking startups struggle; each new product, be it a credit card, loan, or forex card, requires fresh partnerships, navigating multiple layers of risk approval, and often long delays. The very promise of speed and agility was slowed down by the dependency on others.

Big Banks Push Neobanks Out“Today, if you look at our mobile app, we deliver everything a new-age consumer needs. The UI is clean, and it offers everything you would expect from a neobank. There’s no reason for my users to go to a neobank,” a regional head a tIDFC First Bank told Inc42 on condition of anonymity.

And hence, the very offering that the neobanks promised were matched by large banks eventually. With the UI experience proposition gone, there wasn’t much the neobanks could do. So is such an app even relevant today?

Where a conventional bank could quickly offer a customer a loan, a credit card, an insurance product, or a fixed deposit and add to its revenue streams. A neobank, by contrast, had to stitch each of these through separate agreements, often at great cost. This made the journey from customer acquisition to profitability far longer and more uncertain.

“In traditional banks, monetisation comes easily because you can cross-sell multiple products, loans, credit cards, investment products. Banks already have the approvals, algorithms, and infrastructure to plug these in. For neobanks, it’s much tougher. They’re dependent on their partner bank for the liability account, and if they want to offer credit, they have to tie up with another NBFC or obtain a prepaid licence themselves,” said Hyperface’s Jaishankar.

Without the ability to cross-sell a wide range of financial products as easily as traditional banks, monetisation became difficult for the neobanks.

Regulation added further pressure. Initially, co-branded debit or prepaid cards gave neobanks access to valuable customer data, which they could use to personalise services and cross-sell. But as the Reserve Bank of India tightened its scrutiny, data sharing became restricted.

Today, even if a neobank has a card tie-up with a pan-India private bank for instance, the data of that particular card is going to the bank. The neobank doesn’t gain anything here except some touchpoints with the customer.

Further, as the cash deposits in neobanks are typically low, partner banks can’t earn a significant amount through such neobank accounts. This is coupled with the fact that a majority of neobanks couldn’t directly lend, which is the largest revenue source for any bank or fintech startup for that matter.

The double whammy is that a large part of the neobank customer base are individuals who open accounts for short-term needs or as a backup account. It’s rarely the primary account for many and even if that is the case, one can simply move on to the official bank app to manage the account instead of sticking with the neobank.

“For most of the customers, it was like opening a second or third account. And the absence of a banking license creates low trust which further leads to low account balance,” said Abhishek Gandhi, cofounder and CBO of Fatakpay.

Discounts played a role at first when VC funding was flowing, but with this off the table, growth is hard to come by. “Most of the customers we acquired came through heavy cashback offers. Once the funding dried up and the cashbacks disappeared, it became clear that the cohorts we had acquired were low-LTV ones as well,” an ex-employee of Fi Money told Inc42 on condition of anonymity.

Meanwhile, investment tech startups offering mutual funds, SIPs and high-yield investments began to attract the same young, urban customers that neobanks were targeting. With UPI offering free payments, many customers asked: why maintain a second account with a neobank at all?

What makes matters worse is that traditional banks have upgraded their infrastructure and keep pace with emerging tech more closely than before. Neobanks no longer offer the tech advantage they used to.

As we look at the neobanking market, it looks more and more like a wasteland of startups that seemed to have the potential but failed to capitalise on the right market conditions and the VC backing.

Unicorns or not, neobanks like Open, Jupiter, Niyo, Fi and others are fast becoming old news.

Edited by Nikhil Subramaniam

The post Is India’s Neobanking Dream Over? appeared first on Inc42 Media.

You may also like

Premier League ace's agent gives Alexander Isak a run for his money after request to leave

Elton John reveals the song he thought was so bad it was written as a 'joke'

'I found a little-known side to Marbella with pretty streets and charming history'

Oliver! legend ended up penniless after having four homes around the world

The pretty UK village where cars are banned and deliveries are done by sledges